Bbc / hosu lee

Bbc / hosu leeEvery November, South Korea has a storstill for college admissions information.

Shops are closed, flights are delayed to reduce noise, and even the rhythm of the morning commute is slowed by students.

In the afternoon, most of the test takers walk outside the school gates, making sure to comfort and welcome family members who are waiting outside.

But not everything was finished at that time. Even when the darkness completely settled and the night was set, some students were still in the exam room – ending almost at 10pm.

They are blind students, who often spend more than 12 hours taking the highest version of Suneung.

On Thursday, more than 550,000 students across the country will sit for Suneung – a focus for the College Scholastic test truskast (CSAT) in Korean. This is the highest number of applicants in seven years.

The test not only dictates whether people go to university, but affects their job prospects, income, where they live and even future relationships.

Depending on their subject choices, students answer 200 questions in Korean, mathematics, English or foreign natural sciences, and classical China (Classical China

For most students, it’s an eight-hour marathon of back-to-back exams. They started the SunUng test at 08:40 and finished around 17:40.

Blind students with severe visual impairments, however, were given 1.7 times the standard test duration.

This means that if they take the extra foreign language section, the exam will end at 21:48 – almost 13 hours after it started.

There is no dinner break; The examination is ongoing.

The physical bulk of the Braille test papers also contributes to the length.

When every sentence, symbol and diagram is converted to Braille, each test booklet becomes six to nine times thicker than the standard equivalent.

Bbc / hosu lee

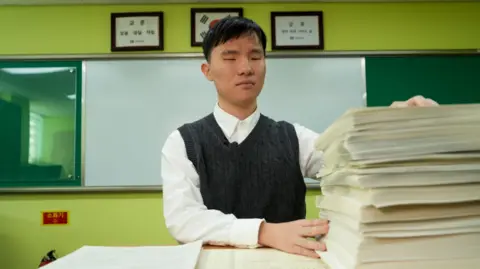

Bbc / hosu leeAt the Seoul Hanbit School for the blind, 18-year-old Han Dongyun is one of the students who will carry the highest version of Suneung this year.

Last year, there were 111 blind owners across the country – 99 with low vision and 12 with severe visual impairments as Data-Hyun – According to Data-Hyun – according to Korea from the Ministry of Education and Korea Institute for the Ministry of Education and Korea Institute for the Ministry of Education and Korea Institute for Curriculum Curriculum and Evaluation.

Dong-Hyun was born completely blind and could not recognize the light.

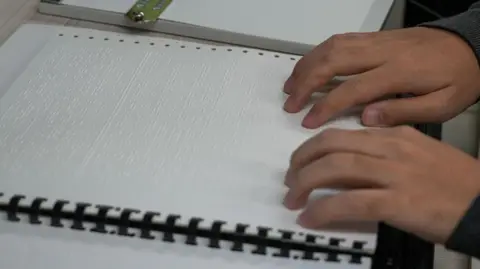

When the BBC met him at his school on 7 November, his fingers quickly moved to a Braille practice booklet.

With a week left before the test, he is focused on managing his stamina and condition. Dong-Hyun took the exam using Braille test papers and a computer screen reader.

“It’s very tiring because the exam is long,” he said. “But there is no special trick. I just follow my study schedule and try to manage my situation. That’s the only way.”

Dong-Hyun said that the Korean language section was especially difficult for him.

A standard test booklet for that section is about 16 pages – but the Braille version is almost 100 pages long.

Even with screen reading software, spoken information is lost as soon as it is heard, unlike text that can be seen and read again. Dong-Hyun must keep the details in his memory as he goes.

The Mathematics Section Is Not Easier.

He had to interpret complex graphs and tables converted to Braille, using only his fingers.

However, he notes that things are better than before. In the past, students had to do almost all the calculations in their heads. But since 2016, the separated owners are allowed to use a Newet in Braille, known as Hansone.

“Just as the students’ views were writing their calculations in pencil, we entered them into Hansone’s Braille to follow the steps,” he said.

Bbc / hosu lee

Bbc / hosu leeAnother student at Hanbit School for the blind, 18-year-old Jeong-Won, who will also be sitting at SuneUng this year, said the final afternoon was the “hardest point” of the day.

“Until lunch, manageable,” he said. “But around 4 or 5pm, after English and before Korean history, that’s when it gets really hard.

“There’s no ruining dinner,” he explained. “We solve problems during the time we used to eat, so the feeling is more tired. However, I continue to go to the end.”

For Jeong-Won, the fatigue compounded by the need to stay more focused on his hands and his hearing.

“When I read Braille with my fingers and also get the information through audio, it feels more tiring than what the students see,” he said.

But students say that the length of the exam and the long hours of study are not the hardest part. The most difficult is the access to study materials.

Popular textbooks and online lectures that students rely on are often out of reach.

There are few versions of Braille, and the conversion of the audio materials requires the files to be available – which are difficult to obtain. In many cases, one has to manually type entire workbooks to make them work.

Online lessons also present difficulties, as many teachers explain concepts using visual notes, diagrams and graphics on the screen.

Bbc / hosu lee

Bbc / hosu leeOne of the most important obstacles, however, is the delay in receiving Braille versions of books prepared by the State – a core set of materials linked to the national exam.

Because of this delay, blind students often receive months later than others.

“Students will see Ebs books between January and March and study them throughout the year,” Jeong-won said. “We received the Braille files in August or September, when the exam was only a few months away.”

Dong-hyun shares the same concern.

“The Braille materials are not completed until 90 days before the exam,” he said. “I’m looking forward to the publication process becoming faster.”

The National Institute of Special Education, which produces the Braille version of the Ebs exam materials, told the BBC that the process should follow the relevant guidelines.

The Institute added that it is “making various efforts to ensure that the students can study without interruption, such as creating and providing materials in different volumes.”

The Korean community in Korea has long raised this issue with the authorities, and plans to file a constitutional petition demanding better access to all Braille books.

Bbc / hosu lee

Bbc / hosu leeFor these students, Suneung is not just a college entrance exam – it’s proof of the years they’ve survived to get where they are.

Jeong-Won describes the exam as “continuity.”

“There’s nothing you can do in life without persistence,” he said. “I think this season is a process of training my will.”

Their teacher, Kang Seok-Ju, watches the students pass the exam every year – and says the perseverance of the blind students is “remarkable”.

“Reading Braille means going straight to the dots on your fingers. The constant wear and tear can make their hands very rough,” he said. “But they do it a lot of the time.”

Mr. Kang encouraged his students to complete instead of regretting.

“This exam is where you pour everything you’ve learned since first grade into one day,” he said. “A lot of students feel disappointed afterwards, but I just want them to leave knowing they did what they could.

“The exam is not everything.”