Editor’s note: This article was originally published on The newspaper of arta CNN style editorial associate.

CNN

–

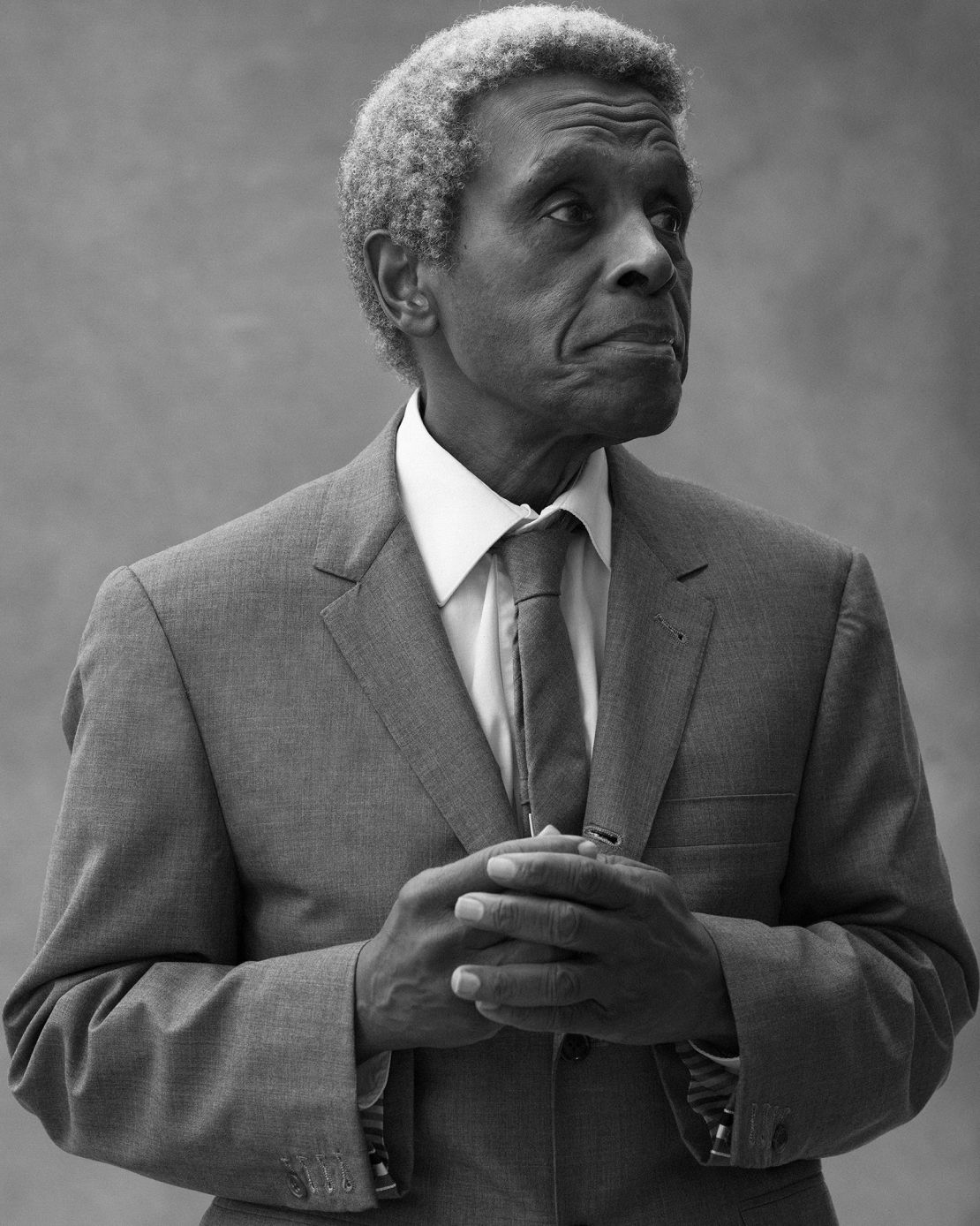

Kwame Braathwaite, the pioneering activist and photographer who helped define the aesthetics of the “black good” movement in the 1960s, died on April 1, aged 85.

His son Kwame Bruthwaite, Jr, announced the death of his father on a Post Instagram That reads in part, “I am deeply saddened to share that my Baba, the patriarch of our family, our Rock and my hero and my hero has passed away.”

Task of BRATHWAITE is the subject of the resurgent interest from curators, historians and collectors in recent years, and his first major institutional retrospective, organized by the Appolerture Foundation in 2019 at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles before touring the country.

BRATHWAite was born in 1938 to Barbadian immigrants, in what he referred to as “the people’s republic of Brooklyn” in New Family and then in South Brontx at the age of 5. He attended the school of industrial art (now the high school of art and design) and, according to BRahwaite’s profiles in T magazine and Viceattracted to the photo twice. The first was in August of 1955, when a 17-year-old Barathwaite encountered David Jackson’s Waunting Photo of a furious Emmett up to his open coffin. The second one was in 1956, when – after he and his brother Elombe co-founded the photographs of Jazz in Africa without using a flash.

Using a Hasselblad Medium-format camera, Holy tries to do the same, learning to work with limited light in a way that enhances the visual narrative of his imagination. Soon he will also develop a technique of darkness that enhances and deepens what appears on the black skin in his photography, paying tribute to the practice of a little darkness in his harlem apartment. BRATHWAite continued to photograph Jazz legends who performed throughout the 1950s and ’60s, including Miles Davis, John Coltrane, John Coltrane, Seludious Monk and others.

“You want to capture the feeling, the consciousness that you experience when they play,” said BRATHWA Aperture Magazine in 2017. “That’s the thing. You want to get that.”

In the early 1960s, along with the rest of Ajass, BRATHWAite began to use his photography and organizing prowess to consciously stop the whitewashing standards. The group came together with the concept of Grandassa models, young black women titled Barathwaite, celebrating and claiming their parts. In 1962, Ajass Organized “natural ’62”, a fashion show held in a harlem club called Purple Manor and featured models. The show will continue regularly until 1992. In 1966, Bruthwaite married his wife Sikolo, a meter he had met on the streets the previous year. The two remained married for the rest of the Holy One’s life.

In the 1970s, BRATHWAITE’s focus on Jazz shifted to other forms of popular black music. In 1974, he traveled to Africa with the Jackson five to document their journey, also taking the historic “foreman of Jungle Ali and George Foreman in the Democratic Republic of Congo that year. The commissions of this period also saw the photo of Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Stone Family, Bob Maramo and other music legends.

In the following decades, Holy continued to explore and develop his method of photography, all through the lens of the “black beautiful” beautiful “Ethos. In 2016, BRATHWAite joined the roster of the Philip Martin Gallery in Los Angeles, and he continued to take pictures in 2018, when he shot the artist and stylist joanne petit-frère for The new yorker.

The 1921 profile of T that was published on the occasion of BRATHWAITE’s return to the Blanon Museum of Art in Austin, Texas he was not interviewed for the article. A different exhibition,”Kwame Braathwaite: It’s good to wait for things“It is currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it will remain until July 24.

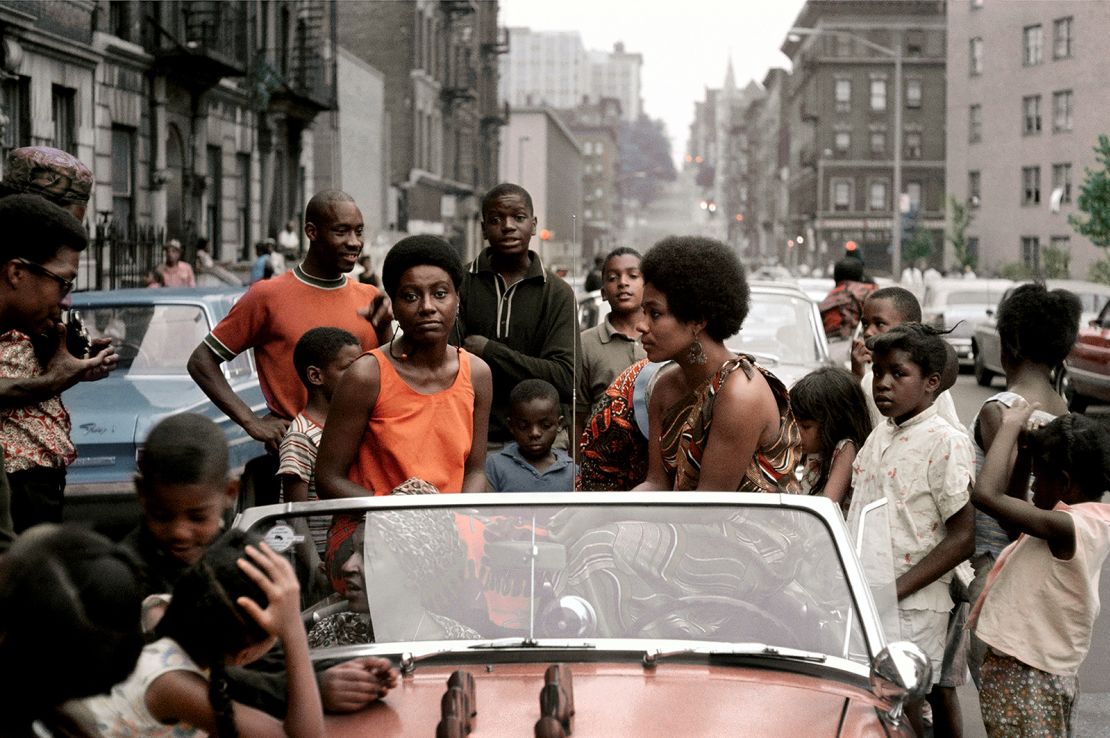

Top Image: Kwame Bruthwaite, “Untitled (Sikolo BRuthwaite, Orange Plactraite),” 1968